No One Listens to an Angry Woman

How softening feminist discourse aligns us with conservative aims

I cut my teeth as a writer during the golden age of the personal essay and the hot-take — a devil’s advocate type of response essay of which I wrote my fair share. The hot-take reduced any subject — whether parenting perspective or a moment of pop-culture — to a simplistic binary argument upon which to plant one’s flag. I have been both on the giving and receiving end of this criticism, both in my internet writing and with my book Fed Up: Emotional Labor, Women, and the Way Forward.

Overall, the hot-take has fallen by the wayside in favor of a less inflammatory iteration of writing — which is often thoughtful cultural criticism that adds depth and nuance to an issue. To be clear, I am in favor of this type of writing. It pulls me from my echo chamber to consider a problem anew. Is there something troubling about the Lolita-esque presentation of Sabrina Carpenter’s performance of unabashed sexuality? Does motherhood have a PR problem because we are finally talking about the more gritty and upsetting aspects of childrearing in a hostile political environment?

These are interesting and thoughtful analyses about what might fall through the cracks when we only talk about one aspect of an issue. But I’ve also noticed, in the context of critiquing feminist writers specifically, there’s a bit of intellectual gymnastics that often lands well-meaning writers in line with conservative talking points. We find ourselves policing the imperfections of an argument, rather than cutting deeper into the heart of the actual problem.

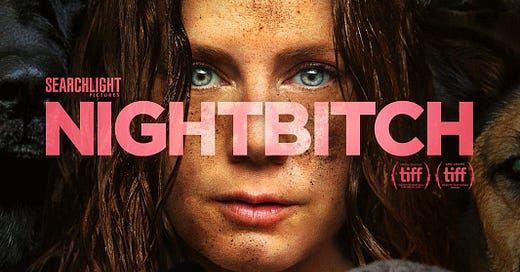

Take the recent body of writing about motherhood, for example. There has been wonderful, incisive writing about the more brutal aspects of motherhood, as well as resonant portrayals of motherhood in film (the recently released Nightbitch lays claim to both, as does Taffy Brodesser Akner’s novel and series adaptation Fleishman is in Trouble). Mother creatives are singing like canaries in the coal mine, warning young women of what lies ahead.

Those warnings, along with the understandable dread that comes with *gestures broadly,* have spurred a wave of young women to reevaluate long-held assumptions about how their lives will unfold: namely whether or not they will become mothers. This has led to predictable (but deeply creepy and upsetting) hand-wringing about declining birth rates that has aptly been described as pronatalist anxiety.

But there is liberal backlash in the discourse around motherhood as well, which aligns with pronatalist aims in its critique. Despite the relatively recent rise of writing that centers the hardships of mothering in a society that devalues caregiving in its myriad forms — there has been a knee-jerk response that cries “but what about the joy and beauty of motherhood?” How can we talk about what is difficult motherhood with such denigration without also acknowledging the deep satisfaction that exists in its midst? How dare we scare women away from becoming mothers?

Firstly, I would say that much of the recent feminist writing about motherhood does acknowledge the both/and of the motherhood experience. But even in cases where motherhood writing doesn’t employ banal caveats about the joy and love that exists alongside the pain, I still find it troubling that the response is often: well have we looked at this issue from all angles? Have we exhausted the gift of perspective? As if what we need is a little “girl, wash your face” injected into our feminism, not to dig deeper into remedies for the systemic issues that cause women pain.

I’ve experienced a similar reaction to my work, when I advocate for shared standards for domestic labor tasks within a home. I hold that women should generally get to retain their standards rather than compromise or “meet in the middle,” because they have likely spent years carefully constructing systems they know work for their families. The standards they set are not arbitrary or symptomatic of “control freak” tendencies. They are tuned in to how to keep things running smoothly - why should they have to meet in the middle with a partner who has historically done the bare minimum?

Well-meaning feminist critiques don’t discount this as untrue, BUT they demand more in-depth consideration of the ways in which women might be falling into the trap of perfectionism. There is more discussion to be had concerning the ways we historically and currently tie women’s worth to their abilities as homemakers. An untidy home reflects poorly on women, not men — therefore we need to untangle that conditioning before we go about setting shared standards.

Again, these are nuanced and worthwhile points to discuss — they add a depth of understanding to the topic of domestic and invisible labor. I talk about them in my book! But again, this sidles too close to the antagonistic argument that we should therefore distrust the domestic standards women have set. It's exhausting to get caught up in these semantics when what we really need is to keep our relentless focus on how we create systemic change. Or even just how we get men to pull their own weight.

Sure, we ought to look at the messages we’ve internalized about domesticity and self-worth, but we also need to understand that this is not the heart of the problem. It’s not that your standards are unreasonable — it’s that we undervalue domestic, mental, and emotional labor because it’s “women’s work.” Regardless of how sincere or well-intentioned, the critique that women’s standards are too high doesn’t serve women as much as it serves men who just don’t want to do the fucking work. Doing the internal work of untangling entrenched gender norms is worth it, but it won’t solve a situation in which your partner is unwilling to pull their weight.

These feminist critiques of feminist critiques aren’t necessarily infighting, but they are reminiscent of the ouroboros, the symbol of a serpent eating its own tail — an unending cycle of self-abnegation and analysis instead of action. But what I find more damning than their circular nature is how this type of discourse almost always effectively weakens arguments that are grounded in righteous rage.

The what-aboutism that abounds in how we approach feminist writing and media seems to opine that angry feminism is too extreme and unpalatable. It suggests our rage needs to be softened with alternative perspectives. It tells us to look at other angles of a topic — to look harder for the silver linings of our own lived experience —so we don’t become mired in a world of feminist killjoy. We don’t want to get carried away here. We don’t want to look like angry women.

No one will listen to an angry woman.

I have spent plenty of time capitulating to the demand that my feminism should be palatable. Too often I waste time trying to evenly weigh all perspectives — carefully considering each facet to prove that my argument is thoughtful and considered. As if keeping an even keel and a broad perspective is a prerequisite for identifying injustice. As if having the most airtight understanding of an issue is what moves the needle toward progress.

Nuanced discourse is important, and I am grateful for it. And I am also wary that we rush past and gloss over the anger that activates feminist discourse in the first place. I’ve noticed that the media often takes these thoughtful pieces and gives them headlines reminiscent of the mid-aughts hot-takes (fun fact, writers don’t choose those clickbait headlines — editorial teams do). Publications encourage the undercutting of feminist thinking to keep us talking in circles — I could write about the ways The Atlantic exploits feminist writing for this specific purpose.

I still want these perspectives to exist in the world, to grapple with the complicated aspects of feminist thinking, so long as we also keep the flame of rage kindled within them. Anger is activating, and action — not endless discourse — is ultimately what we are striving for, isn’t it? That is the purpose of feminist writing: to create tangible change. So I want more angry writing. More righteous rage. Don’t get distracted and put down the torch. We’ve still got a lot of shit to burn to the ground.

Links for further reading:

(who has a LOT of wonderful work about the discourse around motherhood) in conversation with (ditto) - Does Motherhood Have A PR Crisis? - Is Motherhood Hard Work? - How Millennials Learned to Dread Motherhood - Why Weaponized Incompetence is Such a Core Feature of Misogyny - A Lesson In Domestic Labor — How Chores Can Lead to Divorce - Moms Signaling Compliance

I made my husband watch Nightbitch last week. With instructions that it wasn’t a movie to just have playing while scrolling his phoneS. I told him that he needed to focus and really watch it. I then gave him 24 hours to process it before we attempted to discuss it. ::sigh:: I can’t say it was all that satisfying, but I’m hoping the conversation will continue and …percolate.

Wow this is so spot on and well written. I have long twisted the “hot take” on its head by taking a nuanced middle of the road approach (my area of focus is the intersection of health and toxic chemical exposure) but it goes well beyond nuance. I struggle with the angry woman dynamic in how I show up in my personal relationships and work. The price for being perceived or actually angry just feels too high. Very excited to be a new subscriber.